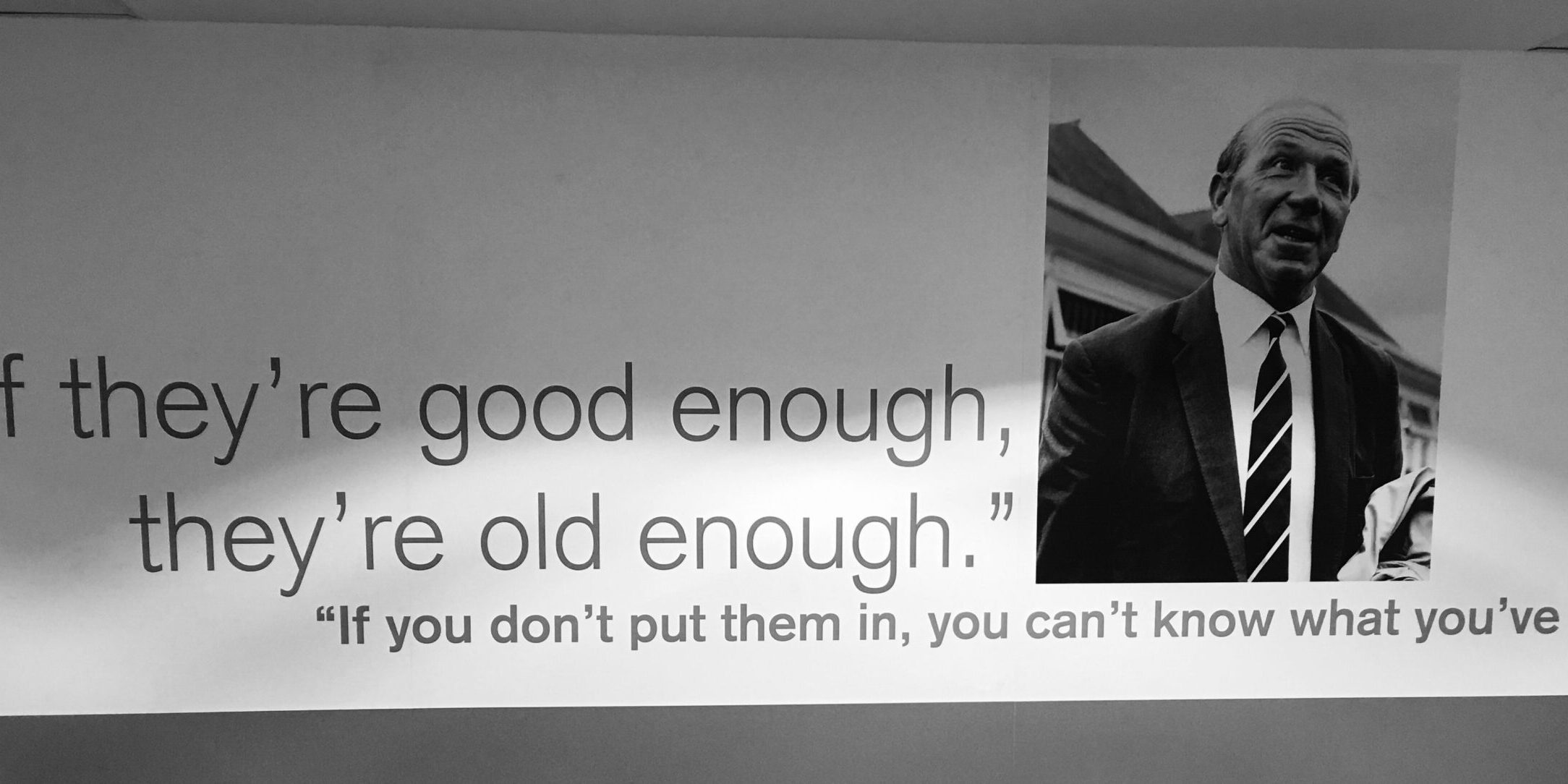

Manchester United’s Carrington Training Center is not only one of the finest youth soccer academies in the world. On every field, the future of the club is evident, as aspiring young players dodge, weave, pass and move the United way. At the same time, everywhere you turn you stare at history. Images of Ryan Giggs, George Best, Bobby Charlton, and David Beckham adorn the walls, and words of wisdom from United legends of the past are plastered on most flat surfaces. One such quote has always stood out to me and I snapped a picture of it on my last visit:

“If they’re good enough, they’re old enough. If you don’t put them in, you can’t know what you’ve got” proclaimed Sir Matt Busby many years ago. “The Busby Babes” as his 1955-56 team was affectionately known, won the English title that season with an 11-point cushion, and an average age of 22. He is credited with creating a tradition at Manchester United of developing and promoting youth into the first team, one famously continued by Sir Alex Ferguson and his famous Class of 1992 that included long time first team stalwarts Ryan Giggs, Paul Scholes, David Beckham, Nicky Butt, and brothers Phil and Gary Neville. Since 1937, Manchester United has had a youth academy product in every single matchday squad.

It takes a special kind of 16-19 year old to have the skill, game understanding, and mental strength to play in front of 80,000 fans in the English Premier league. Christian Pulisic, the rising 18-year-old star of the US Men’s National team and Borussia Dortmund, is another example of a youth player who has jumped straight to the top. But what about youth players, especially very young ones? Should the most talented ones play up an age or two? Should girls train and play with boys? When does this additional challenge help a player’s development, and when does it hinder? These are all questions that are well worth exploring so that parents, coaches and clubs can make the right decisions for the young athletes in their care. But let’s start with this:

Any decision regarding a child playing up an age should be based on what is best for the child.

You don’t coach a sport, you coach a person, and thus every decision is an individual one. It always bothers me when I see organizations with blanket policies disallowing playing up. It equally bothers me when organizations have no policies at all and athletes are scattered across multiple ages for no rhyme or reason. Every youth sports organization should have well-thought out policies in place that allow for athletes to compete not simply against players their chronological age, but their developmental age.This merits some further explanation.

Chronological age is self-explanatory. Most sports separate athletes based on their birth year, or some other arbitrary calendar cutoff such as school year. As we know from the “relative age effect,” this gives a large advantage to those children born closest to that cutoff, especially at very young ages where a January birthday 8-year-old is 11% older than a December-born child. The earlier we make talent selections, the more important this calendar difference becomes. In fact, in a recent conversation with a youth coach from Barcelona’s famed La Masia Academy, I was told that 92% of their Academy kids are born between January and June, with only 8% coming from the latter half of the year!

Chronological age is self-explanatory. Most sports separate athletes based on their birth year, or some other arbitrary calendar cutoff such as school year. As we know from the “relative age effect,” this gives a large advantage to those children born closest to that cutoff, especially at very young ages where a January birthday 8-year-old is 11% older than a December-born child. The earlier we make talent selections, the more important this calendar difference becomes. In fact, in a recent conversation with a youth coach from Barcelona’s famed La Masia Academy, I was told that 92% of their Academy kids are born between January and June, with only 8% coming from the latter half of the year!

Developmental age is the age at which children function emotionally, physically, cognitively and socially. We also know that children grow at different ages. Have you ever coached a 12-year-old boys game in any sport? Did you notice that some look like 10-year-olds and others look like young men? A 12-year-old boy can have a 5 year developmental age swing, as the picture on the left from my friend Nick Levett shows. Those are two 12-year-old boys born a few weeks apart. One certainly has some physical advantages over the other, wouldn’t you say?

Before we discuss playing up specifically, there is one more piece of background needed: Long Term Athletic Development. LTAD models have been developed in most every sporting nation (in the US we call them our ADM, the Athlete Development Model) and outline the various ages and stages of development Our ADM gives us a research-based approach to the physical, social and psychological development of athletes at various stages of their lives. The Canadian LTAD model is best known and is the basis for many others (click here to see it). You can see the US lacrosse ADM here.

Notice how there are age ranges for each stage? That allows for the differences in developmental age for each child. US Lacrosse’s Foundations stage ends around age 12, while the Emerging Competition begins at 11. Basically, that overlap allows for children who start puberty earlier than others (for example, girls usually hit their growth spurt sooner). The importance of these models is they provide a great guide for children playing up vs. those who are held back.

Notice how there are age ranges for each stage? That allows for the differences in developmental age for each child. US Lacrosse’s Foundations stage ends around age 12, while the Emerging Competition begins at 11. Basically, that overlap allows for children who start puberty earlier than others (for example, girls usually hit their growth spurt sooner). The importance of these models is they provide a great guide for children playing up vs. those who are held back.

In education, Vygotsky’s Zone of Proximal Development is the typical model to use regarding where a child’s developmental sweet spot is. In layman’s terms, some children are reading at a 5th grade level in 1st grade and others may be reading right on grade level. The educator is to place the children in these zones where they find the most chance at development – the Zone of Proximal Development. They are challenged, but not overwhelmed. They are also not bored to death. This is really what most organizations dance around but do not understand. Each child should be placed in his own ZPD.

We are often asked about children playing up in age. We have met many parents suffering from FOMO – the fear of missing out – who were worried that if their child did not play up an age, they would be overlooked for high school sports, and have no chance to play in college. They’ve seen other kids who did play up and think that their child should as well. They’ve rarely considered exactly what would make it beneficial for their child, or why it might hinder his or her development. They basically said, “others are doing it, so my kid should too.”

What are some reasons that a child should play up in age? Here are a few factors a coach, a parent, and a sports club should look for in considering whether it is beneficial for a child, and some things to look out for to see if he should remain playing up:

- A child is developmentally (physically) ahead of his or her peers, and tends to rely on physicality rather than technique or thought to have success. This player should be challenged by teammates and opponents who are physical equals. Caution: This child may be socially and cognitively behind, and thus exposed to situations that he/she should not be maturity wise. Some kids struggle with tactical development and understanding the movement and interaction of players. Some are not physically ready to perform certain tasks even though they are big.

- A child is technically and tactically so far ahead of his or her peer group that there is no challenge. This child should be given the opportunity to play against players with the same technical ability and guile so that he/she is challenged to perform at a higher speed of thought and action. Caution: If the physical differences are such that a technically gifted child stops playing the game the right way (i.e. is afraid to dribble or shoot, stops playing confidently) the situation should be re-evaluated. Many players struggle with the physical disadvantage and can develop bad habits.

- When a child starts playing up, they should be eased into the situation. The speed of play at an older age can significantly ramp up the training and playing load on an athlete. Even if they practice and play the same amount of minutes, overuse injuries can happen if you are not careful.

Here are a few reasons that some parents have given me over the years that ARE NOT sufficient to allow playing up to happen, especially as children advance to more competitive environments:

- The kids on that team are part of our carpool (I get it, but hopefully you can form a new carpool. If the carpool is that important, ask permission to go to a practice once in awhile, but don’t play up full time)

- Her best friend is on the team (I am sure they will get plenty of time to play together)

- That team is coached by his favorite coach (it is good to be exposed to many coaches)

- He plays up in other sports (Should an advanced reader should be taking advanced math?)

- Her older siblings were allowed to play up (every child is evaluated as an individual, and perhaps her siblings were older, bigger, stronger, or in an age group where kids were not as good).

- He is in the same grade as those kids on the older team (great, they will get to play together in high school, and perhaps you can guest play once in awhile but in the meantime, we can give the spot to a kid who is the correct age and develop him too)

- Our team has been together for 3 years (often heard when kids transition from recreational to travel programs. Please be patient, and it’s likely that you can make some new friends, and be faced with new challenges instead of being comfortable).

- Parents are generous financial donors (hit like if you feel like you just bit into a lemon!)

I am sure there are many more excuses to play up, but you can get the gist. When it comes to athletic development, the only sufficient reasons for allowing children to play up an age full-time are based on technical, tactical and developmental criterion, and what puts a child in his or her ZPD, not on the whims or dreams of the child’s parents. Every case should be decided on an individual basis, and yes, there are exceptions to every rule (ie. the team at the younger age disbanded). In the end, though, youth sports organizations must be consistent and make these decisions for the benefit of the athlete.

One final caveat is this. If you have a talented athlete playing up a year, or a female who competes with boys, don’t be afraid to slide them down once in awhile and let them remember what it is like to compete against their chronological peers. We tend to only evaluate ourselves against our current peers (i.e struggling Harvard math majors don’t look at themselves as 1%’s, they see themselves as the dumbest kid in the class), so sometimes talented youngsters can lose confidence when always playing against older kids. An age-appropriate game they can dominate from time to time, or allowing talented girls to play against other girls their age, is not a bad thing at all. Again, it must be monitored on an individual basis with parents and coaches working together!

I will leave you with this story. At one of my former clubs, we had a talented, late maturing U15 boy. Not only did he not play up, but we held him back on the club B team that year so he could continue to play the game the right way. He could be a leader, he could take free-kicks, and he could play his preferred position. We let him guest play from time to time, but he was a full-time B team player. He was not happy, nor were his parents initially, but we worked hard to help everyone understand how this benefited the athlete.

One year later he grew and made the top team. Two years he started on a team that won the US Developmental Academy National Championship. Three years on he was the starting center midfielder at an ACC soccer powerhouse. Everyone has their own path. Do not panic when your child’s journey is not the same as another’s.

I realize that “playing up” is a touchy issue for many parents and youth sports organizations, and I hope that we have touched on a few of the issues here. I am sure we have not hit them all, so please, if you have any ideas to share please do so below. Let’s get a great conversation going so when the next talented young player comes along, we can make the decision that best serves his or her needs.

Comments