In 2002, I received a phone call from Patrick, a former high school player I had coached. He had graduated college and was applying to medical school.

“Coach,” he said, “I just wanted to let you know that I am studying for my medical school exams, and it is really hard. But every time I want to put down my books, or if I am in the gym working out, I think of you coaching our team. I picture you telling us “Is that the best you can do? Can’t you do one more? Can’t you do it a bit better?’ and I keep going.”

“Really?” I said. “You still remember that?”

“I think of it everyday,” he said. “Your words and your coaching really have made a huge impact on me, and many of my teammates. So I just wanted to say thanks.”

I didn’t know what to think. I was proud, but more so, I was scared. I was scared because for every kid like Patrick – a player whom I had a great relationship with – I could think of a few players I didn’t serve well. I wasn’t always positive, and I certainly was far more concerned with results than I was for how I made players feel. I reached a lot of kids, but I know others quit because of me and the environment I created. I know some grew to hate a sport they used to love because, as Joe Ehrmann puts it in his amazing book InsideOut Coaching, I was transactional in my coaching, and not transformational.

No one ever taught me differently. They certainly didn’t talk about the relationship part of coaching in traditional coaching education. I am not blaming anyone here. I just didn’t know better.

Every week on our blog, on Facebook and Twitter, we post messages about being better coaches and parents for our kids. We speak about creating a positive, supportive and enjoyable environment. We speak about putting the needs, values and priorities of the athletes first and foremost. We talk about making youth sports an environment of respect and trust, not fear and intimidation. And we speak about focusing on the development of the person and the athlete, and not just the outcome of the game or season.

Yet for many years, I was not that coach. That eats at me everyday.

One phone call changed everything for me. Because of that call, the coach I am today is a far cry from the one I was when I started coaching over two decades ago. It taught me that our influence as a coach is never neutral. It taught me the tremendous impact of our words and actions on kids. Most importantly, it taught me to be intentional about every single thing I did as a coach.

Today I want to share with you eight things I wish I did differently. We don’t get a do over, but we all can “do better.” I share these because I know there are others out there like I was, and I want them to know its OK not to be perfect, as long as you are honest with yourself and not afraid to change.

Here are eight things I wished I never did as a coach, and what I should have done instead:

1. I Focused on Outcomes (Instead of Learning): I was so competitive as a player, so naturally when I started coaching, that carried over. Results mattered. A lot! I judged everything by whether we won or lost, not how we played, or how much we improved. When we lost I questioned my players effort, attitude, focus, you name it. When we won, nothing else mattered. I was willing to compromise a lot to win, including relationships with players, respecting officials, and maintaining the integrity of the sport. That did not serve my players well. Instead of focusing on “did we win?” I should have focused on “did we learn?” Every practice and game is an opportunity to learn, and often in losing we become more reflective learners. It is an opportunity to allow all levels of learner the opportunity to grow. The objective for every young athlete should be to learn, as it promotes a growth mindset and prepares them to win later on in life, when it matters much more.

2. I Focused on Being Serious (Instead of Enjoyment): “This is competitive sports, it’s not about enjoyment! We are developing winners!” How many times did that thought run through my mind when I started coaching? How many times did I look at my bench and not see smiling, happy young athletes, but dour, scared kids who no longer wanted to practice or play because they were afraid of losing, being yelled at for mistakes, and being benched? Too many. Instead, I should have put enjoyment first. Enjoyment is one of the three critical ingredients of athlete development according to Canadian sport scientist Dr. Joe Baker (ownership and intrinsic motivation being the other two). Enjoyment is the happiness you feel when pursuing your potential, and it breeds fearlessness in your athletes. It is not the same as pleasure. Great coaches and parents don’t have to be happy clappy. Long distance runners will tell you that mile 20-26 of a marathon are not very pleasurable, but they still enjoy running. Coaches can focus on enjoyment and be demanding at the same time. They can create challenging, competitive learning environments and still have kids saying “that was awesome, when do I get to do that again?” I wish I learned that sooner.

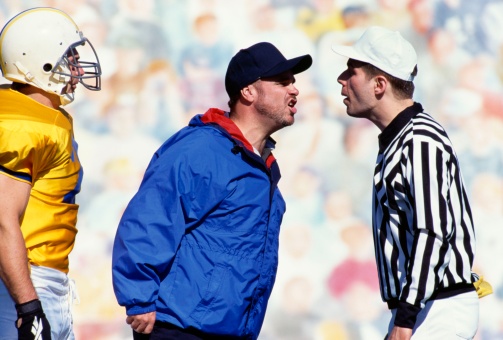

3. I Tried to Inspire by Demeaning (Instead of Being Demanding): My friend Travis Thomas hit the nail on the head with his article “The Fine Line Between Demanding and Demeaning.” I saw my young coaching self in that piece. I tried to inspire athletes by demeaning them. I coached through sarcasm and personal attacks. I thought if they got angry enough, they would perform. Instead of being demeaning, I needed to be a demanding coach. A demanding coach expects more out of people than those people expect of themselves. They say “good, now do it better.” They inspire performance by helping athletes find their inner greatness, instead of thinking that humiliation will drag it out of them. Demanding coaches make their athletes’ eyes shine, while demeaning coaches extinguish the fire. I confused the two. Coaches, please be demanding, not demeaning!

4. I Took Credit for the Good and Blamed Others for the Bad (Instead of the Opposite): I used to be very quick to blame my players for their poor effort, poor focus, and poor execution, and rarely looked at my own role in their losses. I judged myself by my intentions, and my athletes by their actions. Instead I should have given them credit for success, and personally owned more of their failures. When you give athletes ownership for doing things well, they come back wanting more of that. They work harder in practice. They go all in for you, because they know you are all in for them. Instead of saying “look what I did” tell your athletes “look at what you have become.” And instead of blaming athletes for their mistakes, try taking, as ex navy Seal Jocko Willink calls it, “extreme ownership” of issues yourself. When you blame an athlete for a mistake, he or she will likely blame another, and the blame cascades down until no one takes responsibility. But if you take ownership, your athletes will as well.

5. I Did Lots of Talking (Instead of Listening): I was pretty full of myself and my perceived knowledge, and was certain that the more I poured into my players, the better. I was the sage on the stage. I gave all the answers, instead of asking kids “how can I make this better so you will play more?” I was very good at lecturing my kids, when instead I needed to be a better listener. Sometimes our kids actions and words tell us they need a down day, some time off, or even to be pushed a bit harder. Sometimes they will tell you exactly what they need to be inspired, if you take the time to listen to them. Great coaches are people who listen, who interact, and who learn as much from their athletes as their athletes learn from them. I missed out on a lot of learning.

6. I Acted Like a General (Instead of a Teacher): Recently I heard James Leath, head of leadership development at IMG Academy, tell a story of a 7-year-old flag football player being visibly startled by his father yelling “catch it!” a second before the ball reached his son. His son dropped the ball and when he got back to the huddle, said, “Sorry. Throw to someone else, please.” I used to be one of those joystick coaches. I solved every problem on the field. I constantly instructed. I took away responsibility from the kids, and limited creativity, in order to get a result. I was a general, instead of a teacher. I should have guided and mentored them, and accepted failure as a natural part of the learning process. Great teachers do not always give the answer; they say ‘what would you do in this situation?” or “where else could you be now?” As TOVO Academy Barcelona and Cruyff Institute Founder Todd Beane says in this great interview with Skye Eddy Bruce of SoccerParenting.com “If we’re going to be true to the child’s learning process, the intelligence has to be on the field and not on the sidelines. I wish someone told me that in my first coaching course!

7. I Used Fear as a Motivator (Instead of Love): While I didn’t realize it at the time, I tried to lead and motivate through fear and intimidation. “Do this or lose your starting spot! Do this or you are off the team! We better win or you will regret it tomorrow in practice!” Sure, this can work in the short term, but it is not a long term plan. The chances of sustainable growth, participation and enjoyment are slim to none. Instead, I should have been more more like today’s most successful coaches, and motivated through love and connection. Coaches such as Pete Carroll, Steve Kerr, Carlo Ancelotti, Pia Sundhage and Joe Maddon are very demanding, but instead of fear they inspire through love and respect. Think about how you would react if someone threatened your child, or your spouse, or your sibling? You would stand and fight no matter what the odds, because you love them. Could anyone intimidate you or scare you to fight that hard for another? No way. Nothing is more powerful than a bond of love and respect among teammates, coaches and parents working together. No team will fight harder than that team. No athlete will play harder for a coach then one who feels cared for and loved.

8. I Knew it All (Instead of being Humble): I used to sit in the back of the classroom at coaching courses and never asked questions in order to demonstrate that I had nothing left to learn. My problem was that I equated humility and inquisitiveness with weakness, when in fact they are a strength. Many coaches will never admit they are wrong, for fear of coming across as soft. Many people stop learning new things, out of the fear that admitting they do not know it all makes them seem ignorant. Instead of wasting years being a know it all, I needed to be humble, curious, and a life long learner. Every single great coach I have met since starting Changing the Game Project has been a passionate student and lifelong learner! You must model it to your athletes. You can admit when you are wrong. Athletes will forgive you, and better yet, are far more likely to go all in for you and their team if they know mistakes are OK, because even the coach makes them.

I plead guilty to every one of the eight charges described above. But that is OK, because years ago I had a conversation with Patrick that changed my life. I am not the coach I used to be; far from it. I am not perfect, and I am not supposed to be. At times I still struggle to say “what did you learn” when we lose 8-0. I still have a hard time biting my tongue and watching a goal get scored instead of joy sticking a player into position. I sometimes fail to own my mistakes, listen well, and be humble.

But all that is OK because my journey is not over. It should never end. I don’t want to have a 40 year coaching journey by reliving the same season forty times. I want every season I coach to be better than the last.

Everyday I am trying to get better. My players know it. Their parents know it. And I know it.

Coaches, we owe it to the kids to honestly evaluate our coaching, and if necessary hit the reset button like I did. Have the courage to change. Take ownership of who you are and what you do. Be a difference maker.

Be better!

Comments